From Internal Ports to External Domain

Intro

It recently occurred to me that most people don't actually know how to plumb the great internet pipes from one end to the other. To me this stuff is pretty simple and straightforward. That's a Matt bias there, my bad y'all. At the risk of being patronizing, I will be thorough in my explanations here.

Domain Registrar

Let me start by talking about how a public domain works, since not everyone has purchased a domain before. I once, long ago, selected GoDaddy, so I have stayed there, though this is not an endorsement of them. Anyway, here's a sample test domain called testy-cal.com, nothing inappropriate about that at all, no sir, just a test domain in California, yup. Once you have purchased a domain, you need to find the place in the registrar's website where you can edit DNS. This is what it looks like for GoDaddy:

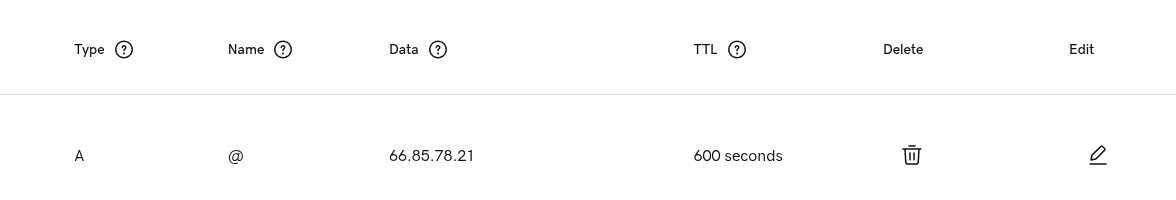

From there, you can assign all DNS records for your domain. For matt-cloud.com, this all points to the external IP address that I have assigned for this function. Here is an example of that for Matt-Cloud. This is some of the primary wizardry needed to get a website going. This flow here allows anyone in the world that puts matt-cloud.com into their web browser to get directed over to my little home at Joe's.

In order for things like kb.matt-cloud.com or auth.matt-cloud.com or all the other stuff to also resolve to an IP, I either have to set up each one, one-at-a-time, or set up a catchall record. The catchall record is a beautiful thing because I am lazy and don't wanna deal with all that shite. This is what the Matt-Cloud catchall record looks like. This just means that *.matt-cloud.com will redirect to the root page IP address unless I configure a different record on GoDaddy to overwrite this. Super easy stuff, but if you don't know then it's a mystery, right?

External IP Address

This is something that bears some text. All internet connections have an external IP address somewhere. At the risk of insulting your intelligence, here's an overview of how that works on a typical home cable internet connection. You get your physical gateway from Comcast, and that has an external IP address on Comcast's network somewhere from the Coax connection. This IP is, in theory, route-able from anywhere on the internet, barring any traffic shaping from the ISP/Government. This IP is also, despite being an external IP, not a static IP, and is subject (though unlikely to) change at any time. The gateway device then has NAT-ing, routing, DHCP, and firewall services on it, and will hand out internal IPs to your devices such as 10.0.0.100, and will have an internal IP of something like 10.0.0.1 as the internal gateway address. In almost all cases, this is how everyone's home internet is set up, and that external IP doesn't host any services and doesn't allow any traffic into the home network. To get a reliable external IP route-able from anywhere requires a bit more than just using the external IP from your home gateway. I believe an option is using Cloudflare, though this is not a service I have used before. For home-based servers, you can get business-class internet with public static IP addresses. If you are dedicated and willing to spend the money, you can build a real server and rent space in a datacenter like I do. My server gets a network cable from the datacenter, and I get some static IPs to do with as I please within the confines of terms of service of course. If you just want to host a virtual server in someone else's cloud, then that can also use cloudflare or presumably the cloud provider can assign you static external IP addresses.

Firewall and Network

If your external IP address comes in the form of a network cable from some ISP, then you need a firewall. There are so many varieties to choose from, and I am a pfSense simp, despite the shady shit that happened moving from mostly community to mostly commercial. The OS is still free and it works exceptionally well. If your tinfoil hat is thicker than mine, you can check out OPNsense, though I have not. There is also OpenWRT which is harder to use than OPNsense and so I haven't messed with it much. dd-wrt is known for being able to replace proprietary firmware to make old junk less junk. Then there's Unifi's offerings, though I haven't used their stuff for firewalling before. In the commercial world there's Sonicwall, Fortinent, Cisco, Palo Alto, and so many others. Anyways... the important thing is that for you to host a website, you need to forward ports 80 & 443 from the external IP to your web host. Since this is 2025 and we aren't savages running HTTP websites, I recommend using a docker-based proxy that can automatically deal with Let's Encrypt certificates. My old web server that was just an Ubuntu VM with Apache installed had the jankiest setup to make Let's Encrypt to work, and now you just need a docker container and can do that shit in the web, amazing, love it. I drew a diagram that kind of illustrates the entire flow of this stuff and the server end a bit too. The IPs and domains are all made up, but the point does matter. Effectively, a client computer out on the internet types https://kb.domain.com and that client looks up the IP for kb.domain.com as 12.34.56.78, and then it checks port 443 on 12.34.56.78 for https traffic. The server then needs to have some program hosting https traffic that is made accessible from 12.34.56.78 on port 443. I realize this is a very obvious statement, but the point is critical enough that it bears stating. There are many ways to accomplish this flow, and Matt-Cloud has 3 different services dealing with https certificates for different external IPs, but the Billionaire's share of this is done by the proxy container NPM. This is where almost everything on Matt-Cloud flows through. This is linked using NAT on the Firewall. The internal ports don't actually need to be 80 & 443, but I use them anyway with my proxy since it makes it more obvious.

This is what some firewall NAT rules look like. Aside from the main proxy, the web server and Matt-Cloud Drive handle their own HTTPS certificates. The importance of this is that Let's Encrypt authenticates a certificate by matching the external IP of the request for the certificate to the DNS entry for said certificate. Thus, if I want a certificate for auth.domain.com, and I request this certificate from the IP 12.34.56.78, then the IP for that DNS entry must be 12.34.56.78. The NPM container will do all this automatically, and it's a docker container. Since I maintain a singe VM for all my docker containers, this means there is a massive virtual private network (not to be confused with a VPN like IPSec or SSLVPN) running in the docker host's kernel. This private network is unreachable even from the internal network of the docker host, but it is reachable from the NPM container. This means the discrete networks assigned for docker containers can have proxy domains easily assigned to the internal IPs and ports of the various containers. An example of a service using a non-default network is Matt-Cloud Drive. You can see here the sample subnet is 10.20.1.0/24. If the docker server has the IP as in the scrappy picture of 172.16.1.10, then 172.16.1.1 can not reach 10.20.1.0/24, though 172.16.1.0/24 is reachable from the other way because the docker host acts like a router and firewall between all these networks. Thus, the proxy container could reach this subnet and handle the certificates, if the certs for Matt-Cloud Drive weren't one of the two exceptions to the proxy dominance.

docker-compose.yaml - NPM

This is the docker-compose file to spool up an NPM container

# docker-compose.yaml

services:

nginx-proxy:

image: jc21/nginx-proxy-manager:latest

container_name: nginx-proxy

restart: always

ports:

- "172.16.1.10:80:80"

- "172.17.0.1:81:81" # management port, this config makes it only reachable from the docker network stack

- "172.16.1.10:443:443"

volumes:

- /media/docker/proxy/npm_data:/data

- /media/docker/proxy/npm_letsencrypt:/etc/letsencrypt

- /bin/ping:/bin/ping:ro # for troubleshooting

network_mode: bridgeHow easy is it to request a certificate? It's this easy, just ask, and if everything is pointed in the right place, then it will just work.

I have another artisinal masterpiece of glory showing a bit of how a docker server works. The network stack can do a bunch of stuff, including Routing and Firewalling. The virtual bridge networks that are hooked into the network stack here are all reachable from each other, but the eth0 can be thought of as the WAN connection on this. If a firewall is not set up, and this IP is set as the gateway address on another network on the system, then those networks might be reachable.

No Comments